One of the biggest equipment purchases a machine shop will make is switching from manual to CNC lathe operations. This decision is unsettling for good reason—you might be giving up decades of demonstrated proficiency in manual machining in favor of costly and intimidating computer-controlled technology.

However, businesses that put off this change for too long watch rivals take jobs they can’t effectively bid on, deal with operator shortages they can’t cover, and forfeit profits they can’t afford to lose. The strategic question is not whether to switch, but rather when and how to do it.

After 37 years of assisting manufacturers with equipment transitions, we have witnessed every possible situation: businesses that waited too long and lost market share, shops that made the switch too soon and found it difficult to justify the investment, and astute manufacturers who strategically adopted CNCs and dominated their markets.

The practical realities of CNC Lathes versus manual lathe work are exposed in this guide, which cuts through the emotional attachment and marketing gimmick. You’ll discover how to overcome reasonable concerns, identify the signs that switching makes financial sense, learn about the true cost differences, and find a transition strategy that maximizes return on investment while minimizing risk.

Understanding the Fundamental Differences

Understanding what changes when switching from manual to CNC lathe operations is necessary before deciding when to make the switch.

Manual Lathe Operation

Skilled operators are needed to oversee every step of the cutting process on manual turret lathes and traditional engine lathes. The machinist manually changes cutting tools, uses mechanical systems to modify spindle speeds, physically controls handwheels to control carriage movement, and keeps an eye on the cut through experience and direct observation.

There are some benefits to this practical method. Skilled manual machinists can handle one-off parts without incurring programming overhead, adjust strategies mid-cut when they sense something is off, and quickly adjust to unforeseen circumstances. The equipment itself can be used in practically any shop setting, has a lower initial cost, and requires less complex maintenance.

However, there are inherent limitations to manual operation. Part complexity peaks at what a competent operator can consistently generate while keeping an eye on several variables at once. The physical limitations of manual control and human reaction time limit production speeds. The skill and attention of the operator are the only factors that determine consistency in quality; as fatigue sets in, the same operator produces slightly different parts throughout the day.

CNC Lathe Operation

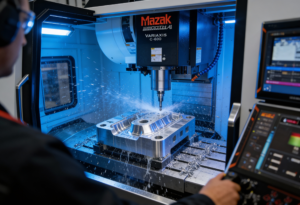

CNC Lathes take the operator out of direct control of the cutting process. Rather, programmers write comprehensive instructions that outline each tool movement, feed rate, spindle speed, and cutting parameter. These programs are carried out by the machine with an accuracy that cannot be duplicated by human operators.

Current CNC lathes, such as the Haas ST series, have features that manual machines just cannot match: precise thread cutting without human timing, automatic tool changing that takes only a few seconds, simultaneous multi-axis interpolation for intricate contours, and live tooling that executes milling operations while the turning cycle is underway.

When parts need precise tolerances for several features, intricate profiles that would require a great deal of manual skill, or production runs where consistency across hundreds or thousands of parts is important, the CNC advantage becomes evident. A properly programmed CNC lathe regularly achieves ±0.0005″ or tighter tolerances without operator intervention, whereas a skilled manual machinist might maintain ±0.002″ tolerances with careful attention.

The Real Cost Comparison

Understanding true costs requires looking beyond sticker prices to examine total operational economics over meaningful time periods.

Initial Investment Analysis

Depending on its size and features, a high-quality manual lathe can cost anywhere from $15,000 to $50,000. A similar CNC turning center costs between $75,000 and $200,000 for brand-new equipment, or between $35,000 and $100,000 for well-maintained used equipment. Many shops are deterred from giving CNC serious consideration by this initial cost difference of 3–5 times.

Nevertheless, this comparison overlooks a number of elements that have a significant impact on real economics:

Tooling Investments: The initial setup of CNC lathes requires $5,000 to $15,000 in tool holders, insert tooling, and possibly live tooling components. Traditional cutting tools and tool holders, which cost between $2,000 and $5,000 for a full shop setup, are required for manual lathes.

Installation Costs: For consistent accuracy, CNC equipment needs sturdy foundations, suitable electrical service (usually 230V or 460V three-phase), and occasionally climate control. For a proper installation, budget between $3,000 and $10,000. With little setup, manual lathes can be used in nearly any type of shop.

Training Investment: Operators must receive instruction in CNC programming and operation, either through formal courses that cost $2,000 to $5,000 per person or through on-the-job training that lowers productivity while learning. Usually, manual machinists gain their skills through years of apprenticeship, but their higher pay reflects this.

Operating Cost Reality

Operating costs drastically change the equation after equipment is installed:

Labor Efficiency: For moderately complex tasks that need continuous attention, a manual machinist may produce 15–25 parts in a shift. With occasional operator supervision, a CNC lathe with bar feeder can produce 100–300 parts per shift, enabling one person to keep an eye on several machines. Higher equipment costs are swiftly outweighed by this 5–10X productivity difference.

Scrap Reduction: Human error, poor tool wear judgment, and basic errors usually result in 3-7% scrap rates in manual operations. With the right programming, CNC operations routinely produce less than 1% scrap, saving thousands of dollars in material waste every year.

Tool Life Optimization: CNC machines maximize tool life and surface finish by continuously operating at optimal speeds and feeds. Throughout the day, manual operators adjust parameters, frequently operating conservatively to prevent errors, which ironically can shorten tool life by creating unsuitable cutting conditions.

Overtime and Second Shift Economics: Skilled workers must be on hand during all production hours for manual operations. Even in smaller shops, second shifts and weekend work are financially feasible due to CNC machines’ ability to operate unsupervised or with little supervision.

Clear Signals It’s Time to Switch

Adoption of CNC is financially evident in some circumstances. Delaying the transition actively costs you money if you’re dealing with multiple of these issues:

Signal #1: Repeating Parts Over 25 Pieces

CNC economics becomes attractive when you are producing runs of 25 or more identical parts on a regular basis. The consistency and speed benefits swiftly surpass manual production, and the programming time is amortized over the production quantity.

Compare realistic CNC cycle times (usually 40–60% of manual time once programmed) with your current manual production time per part. The time savings typically outweigh the programming overhead at 25 pieces. The benefits of CNC become overwhelming at 50+ pieces.

Signal #2: Tolerance Requirements Under ±0.002″

CNC precision becomes essential rather than optional if customers are requesting tolerances that are more than ±0.002″ or if you are routinely discarding parts because of tolerance problems. Tight tolerances can be achieved by manual machinists, but it takes extraordinary skill and ideal circumstances to maintain them across production quantities.

Without extra effort, CNC machines regularly maintain tolerances of ±0.0005″ throughout full production runs. Bidding opportunities for precision work that manual operations just cannot consistently produce are made possible by this capability.

Signal #3: Skilled Operator Shortage

It’s getting harder to find skilled manual machinists. As fewer young people enter the field, the average age of manual machinists continues to rise. CNC technology offers an alternative to paying top dollar to retain aging operators or struggling to fill manual machinist positions.

Unlike manual machining, CNC operation necessitates programming, setup, and troubleshooting skills instead of handwheel manipulation. Instead of taking years to develop skilled manual machinists, you can train motivated individuals with mechanical aptitude to operate CNC equipment in a matter of weeks or months.

Signal #4: Complex Features Requiring Multiple Setups

Parts that need to be manually set up several times, such as turning between centers, flipping parts, or drilling on a different machine, waste time and cause errors in accuracy every time the setup is changed. Complex parts can be completed in a single setup by CNC lathes with live tooling and sub-spindles, significantly cutting cycle time and increasing accuracy.

Compute the handling time, setup time, and accuracy loss if you frequently move parts between machines or re-chuck for various operations. Even for relatively small production quantities, these hidden costs frequently make CNC investment worthwhile.

Signal #5: Turning Away Work Due to Capacity

You’re losing money that could be used to buy CNC equipment when you turn down quotes because manual production can’t meet delivery deadlines. Keep track of the yearly value of the work you are unable to bid on or must decline; if it is more than $50,000, CNC capacity will probably pay for itself in two to three years.

This signal is especially significant because it shows not only the current loss of revenue but also the erosion of market position as consumers move to rivals who can satisfy their needs.

Signal #6: Quality Claims or Rework Exceeding 3%

Rework or quality claims on a regular basis show that your manual process variation surpasses customer expectations. Determine your yearly rework expenses, taking into account labor, supplies, and harm to your reputation. CNC investment is directly offset by this “cost of poor quality.”

Most variation-related quality problems are eliminated by CNC consistency. Assuming appropriate maintenance and tool management, CNC program parts 1, 100, and 1000 function identically.

Common Concerns and Practical Realities

Being aware of valid worries enables one to deal with them in a practical manner rather than allowing fear to stop wise choices.

Concern: “CNC Programming Is Too Complex”

Reality: Conversational programming is a feature of contemporary CNC controls, such as Haas’s NGC system, that helps operators perform routine tasks. For many common parts, you can write functional programs at the machine without the need for computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) software.

CAM software has grown more user-friendly for complex tasks, and many now provide small shops with free or reasonably priced options. Furthermore, pre-existing program libraries from prior owners are frequently included with used CNC lathes, offering templates that you can alter for comparable parts.

Basic proficiency in programming usually takes two to three months, solid capability takes six to twelve months, and true expertise takes one to two years. Basic competence, however, is adequate for instant productivity on simple tasks.

Concern: “We’ll Lose Flexibility for One-Off Parts”

Reality: Although this worry is valid, it exaggerates the limitations. Programming time is absolutely necessary for CNC machines, but not for manual operations. Nonetheless, a number of factors lessen this drawback:

For seasoned programmers, quick programs for basic components take 15 to 30 minutes. Writing thorough manual operation sheets may take longer than conversational programming at the machine. Even “one-off” parts frequently repeat occasionally, making stored programs valuable. Many shops find they produce more one-off work than they realized.

Furthermore, you don’t have to stop using manual equipment right away. Both manual and CNC lathes are used in many shops. While routing the proper work to CNC, manual equipment is used for true one-offs and fast modifications. View our entire selection of lathes, which includes both manual and CNC models.

Concern: “Maintenance Costs Will Kill Us”

Reality: The truth is that although CNC lathes need more complex maintenance than manual machines, the expenses are predictable and controllable. Preventive maintenance, sporadic repairs, and software upgrades are typically covered by annual maintenance, which costs three to five percent of the equipment’s value.

This expense must be weighed against the value of decreased scrap, increased productivity, and lower labor costs, as well as manual lathe maintenance, which is typically 1% to 2% per year. When everything is taken into account, the net economic equation clearly favors CNC.

Purchasing high-quality used CNC equipment from reliable vendors greatly allays this worry. With maintenance needs no worse than those of new machines, a well-maintained used Haas ST-20 or ST-30 offers years of dependable service at a fraction of the price of new equipment.

Concern: “What If the Operator Quits?”

Reality: In actuality, this worry supports CNC rather than contradicts it. A small shop can be completely destroyed by losing a skilled manual machinist who is familiar with your parts, procedures, and peculiarities. Their body of knowledge is frequently unique.

Knowledge about CNC operations is recorded in setup sheets, tool lists, and programs. Instead of attempting to recreate tribal knowledge, the replacement operator uses this documentation when the original operator departs. While it takes years to find and train replacement manual machinists, it only takes weeks to months to train replacement CNC operators.

Making the Financial Decision

Use this framework to evaluate CNC adoption objectively:

Step 1: Quantify Current State

- Annual labor cost for turning operations

- Material scrap costs

- Lost opportunity from declined work

- Rework and quality claim costs

- Overtime and premium shift costs

Step 2: Project CNC Economics

- Equipment cost (used machines offer 40-60% savings versus new)

- Installation and tooling investment

- Training costs

- Reduced labor hours (realistic productivity gains)

- Reduced scrap rates

- New work capture potential

Step 3: Calculate Payback Period Simple payback = (Equipment Cost + Setup) / (Annual Savings + New Revenue)

If payback is under 3 years, CNC adoption makes strong financial sense. Under 2 years represents compelling economics that should drive immediate action.

Step 4: Consider Strategic Factors Some advantages resist quantification but dramatically impact competitiveness:

- Market positioning versus competitors

- Capability to bid on emerging work types

- Succession planning as manual machinists retire

- Employee satisfaction working with modern equipment

The Transition Strategy That Works

Smart manufacturers don’t switch abruptly—they transition strategically:

Phase 1: Add First CNC While Keeping Manual (Months 1-6)

Purchase one quality used CNC turning center, preferably a versatile model like a Haas ST-20 with live tooling. This provides:

- Learning opportunity without betting the entire operation

- Fallback to manual equipment during learning curve

- Immediate capacity expansion for suitable work

- Proof of concept for your specific applications

Route obvious CNC-suitable work to the new machine: production runs over 25 pieces, parts requiring tight tolerances, and work with complex features. Keep manual lathes running on one-offs and quick-turn work.

Phase 2: Build Programming and Operating Competence (Months 3-12)

Invest in formal training for at least two operators/programmers. Cross-train so equipment doesn’t sit idle when one person is unavailable. Build program libraries for recurring parts. Document setups, tool lists, and procedures.

During this phase, gradually shift work from manual to CNC as confidence and competence increase. Track actual productivity, scrap rates, and cycle times to validate the investment with real data.

Phase 3: Add Capacity or Specialization (Months 12-24)

Once the first CNC lathe runs at 60%+ utilization and you’ve mastered basic operations, consider:

- Adding second CNC lathe for capacity

- Upgrading to larger or more capable model

- Maintaining one manual lathe for specialty work

- Complete transition to CNC-only operations

This staged approach minimizes risk while building the capability and confidence needed for long-term success.

Conclusion: Strategic Timing Drives Success

Making the switch from manual to CNC lathe operations is not a “all or nothing” or “now or never” choice. Astute manufacturers make strategic transitions, retaining manual options for tasks where it makes sense and introducing CNC capability when their unique circumstances warrant the investment.

Repeated production runs, strict tolerance requirements, a lack of skilled operators, complex part features, and capacity limitations are all clear indicators that CNC adoption will boost competitiveness and profitability. Ignoring these indicators jeopardizes long-term viability and weakens market position, not to mention traditional craftsmanship.

To reduce investment risk and gain access to tested technology, start with high-quality used equipment from reliable dealers. The financial decision is made much easier by the fact that a well-maintained used Haas ST series lathe offers the same capability as new equipment at 40–60% of the cost.

Manufacturers who stick with manual processes the longest will not be the ones who prosper over the next ten years. They will be businesses that carefully embraced CNC technology when their operations warranted it, developed the skills necessary to use it efficiently, and set themselves up to meet ever-tougher client demands.