A Practical Buying Guide for Growing Shops

I recently read about a California precision shop that bought their first multitasking machine back in 2003 to solve a problem: a screw machine that couldn’t handle the part geometries they needed. Twenty years later, they’re running ten of them and have grown 250% in eight years.

The article: https://www.mmsonline.com/articles/the-value-of-a-third-turret-for-multitasking-machines-2

That’s a success story. But here’s what caught my attention: it took them two years to fully trust the machine’s capabilities. For the first few months, they only used one turret at a time on a twin-turret machine. They had all that capability sitting there, and they were afraid to use it.

That’s a real issue when shops are looking at used multitasking machines. The potential is there, but so is the learning curve. And when you’re spending $60,000 to $150,000 on used equipment, you need to know what you’re getting into.

What “Multitasking” Actually Means

The term gets thrown around loosely, so let me clarify what you’re actually looking at when someone says “multitasking machine.”

At the basic level, you have lathes with live tooling. You can do some milling, drilling, and tapping without moving the part to a second machine. Most shops already know what this looks like, and it’s been around for decades.

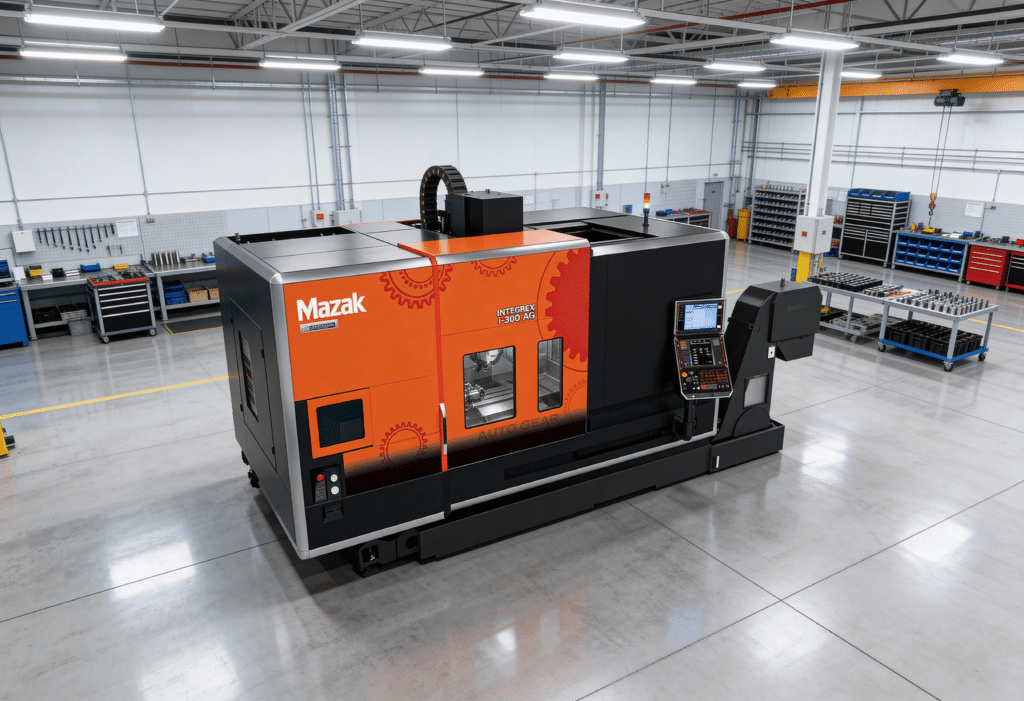

True multitasking machines are different. They combine full turning center capability with legitimate milling spindle power—we’re talking B-axis heads that can approach the work from multiple angles, Y-axis movement for off-center features, and often twin spindles that can work simultaneously. Machines like the Mazak INTEGREX, Okuma Multus, Nakamura-Tome WT series, and DMG Mori NTX fit here. These aren’t lathes that can do a little milling. They’re platforms that genuinely replace both a turning center and a machining center.

Some shops are now even integrating directed-energy deposition for hybrid additive work, though that’s still rare in the used market. The technology keeps expanding, but the core idea remains: get the part done without moving it.

The difference between these levels matters because each step up brings more capability but also more complexity in programming, setup, and maintenance. A shop that needs basic live tooling shouldn’t be paying for B-axis capability they’ll never use.

The Real Case for Multitasking

|

30-50%

Cycle Time Reduction

on complex parts

|

75%

Setup Time Savings

depending on complexity

|

0

Tolerance Stack-Up

done-in-one precision

|

|

⏱

Eliminate Part Handling

No moving parts between machines. No re-fixturing. Time savings compound with every operation you consolidate.

|

📊

Job Shop Math

Running batches of 50-200 parts? Setup is a huge percentage of total job time. Cut it by 75% and effective capacity goes through the roof.

|

✓

Aerospace & Medical Grade

Features that reference each other get cut in the same setup. Often the only way to hold critical tolerances.

|

|

⚠

|

What the sales pitches don’t tell you

These gains only materialize if your parts actually need multitasking. Simple two-axis turned parts? A multitasking machine is expensive overkill.

|

Who Should Actually Consider This Technology

Multitasking makes the most sense for shops running complex parts that require both turning and milling. If you’re currently shuttling parts between a lathe and a VMC, and tolerance or lead time is costing you jobs, multitasking solves a real problem.

Shops that need to consolidate operations for traceability reasons—medical, aerospace, defense work—often find multitasking essential. The fewer setups, the better the documentation trail and the tighter the tolerances you can hold consistently.

I also see this technology making sense for shops with skilled programmers but limited floor space. One multitasking machine can genuinely replace two or three conventional machines. That’s significant if you’re paying for square footage in expensive markets.

And if your customers are asking for capabilities you don’t have, a used multitasking machine can open doors. The work that requires B-axis milling and done-in-one processing pays better than commodity turning. A used machine at $80,000-$120,000 gets you into that work without the $400,000 new machine investment.

Who Should Think Twice

I’m going to be direct here because I’ve seen shops make expensive mistakes.

If your parts are simple, you don’t need this technology. Two-axis turning? Basic mill work? A good twin-spindle lathe with live tooling handles that at half the price and half the complexity.

If your programming expertise is thin, multitasking will frustrate you. These machines require solid CAM capability—software that can handle multi-channel machining—and operators who understand how to keep two spindles and multiple turrets working together without collision. The California shop I mentioned has a whole programming department. If you’re a ten-person shop where the owner does the programming after hours, think hard about whether you can support this technology.

If your volume is extremely high on simple parts, dedicated machines are still faster. Multitasking shines in the low-to-medium volume range where flexibility matters more than pure speed.

And if your maintenance team is already stretched, adding a multitasking machine adds risk. More axes, more turrets, more spindles means more potential failure points. These machines need proper attention—proper meaning scheduled, not when something breaks.

What to Look For in Used Machines

When we evaluate multitasking machines coming through our facility, we’re looking at specific things that matter for long-term performance.

Hours on the spindles tell part of the story, but you need hours on both the main spindle and the milling spindle. A machine with 15,000 hours on the turning spindle but only 3,000 on the milling spindle tells you something about how it was used. That shop was doing mostly turning work. The milling capability is less worn, but it also wasn’t really tested.

The B-axis and Y-axis condition matters enormously. These are the money components on a multitasking machine—the features that make it more than just a lathe with live tooling. Ask about backlash measurements. Request ball bar test results if available. B-axis roller gear drives and cone couplings wear over time, and that wear shows up in your parts as positioning error.

Turret indexing accuracy on twin-turret machines needs checking on both turrets. Sloppy turret positioning compounds through every tool change. If the turret can’t repeat within a tenth, your parts won’t either.

Control system age makes a bigger difference than some buyers realize. A 2008 machine with a Fanuc 18i-TB is very different from a 2016 machine with a Fanuc 31i-B or Mazatrol SmoothX. Newer controls offer better simulation, easier programming, and features like collision avoidance that protect expensive spindles from programming mistakes. If your programmers are learning on this machine, collision avoidance alone might be worth paying more for a newer control.

Thermal history is something most buyers don’t ask about. Machines that ran lights-out production may have more total hours but more consistent thermal cycles—they heated up and stayed warm. Machines that sat cold overnight and then ran hard every morning have different wear patterns from the constant thermal cycling. Ask about the previous shop’s operating schedule if you can.

What the Used Market Actually Looks Like

The used market for multitasking machines is active, and I’ll give you realistic price ranges based on what we see.

Entry-level used multitasking—twin-spindle, twin-turret machines with Y-axis from before 2015—typically runs $40,000 to $70,000. Machines like the Nakamura-Tome WT-150, older Mazak INTEGREX 200 series, or Doosan Puma MX fit here. These are solid machines for shops making the step up from conventional equipment. They won’t have the newest controls or the slickest programming interfaces, but the fundamental capability is there.

Mid-range used multitasking—machines with B-axis milling heads from 2015 to 2020—runs $70,000 to $130,000. This is where you find capable machines like the Nakamura-Tome Super NTY3, Mazak INTEGREX i-200, Okuma Multus B300, and DMG Mori NTX. True five-axis milling capability opens up complex parts that basic mill-turn machines can’t touch.

Premium used multitasking—large envelope machines that are automation-ready and built after 2020—commands $130,000 to $250,000. These have full five-axis capability, bigger tool magazines, and the integration points for automation. The value is there if your parts need the capability and your volume justifies it.

For context, comparable new machines run $300,000 to $500,000 and up. A well-maintained used machine at 40-60% of new price represents significant savings while delivering the same fundamental capability. The machine doesn’t know it’s used.

The Major Brands: Honest Assessment

Every brand has its partisans, and I’m not here to tell you which one is best. But I can tell you what we actually see with each.

Mazak INTEGREX has the largest installed base of any multitasking platform. That means more used machines available when you’re shopping, more operators who already know the Mazatrol control, and strong parts availability. The downside is that service costs can be high, and older Matrix controls have a steeper learning curve than newer Smooth systems. If you’re buying a pre-2015 INTEGREX, budget time for your programmers to adapt to Mazatrol if they’re coming from a Fanuc background.

Nakamura-Tome built their reputation on rigidity and precision. Shops doing tight-tolerance medical and aerospace work often gravitate here. The machines hold accuracy well even at higher hours, and reliability is excellent. The trade-off is a smaller dealer network than Mazak. Methods Machine Tools handles Nakamura in most of the US, so your support experience depends heavily on your relationship with Methods in your region.

Okuma Multus machines offer the Thermo-Friendly Concept thermal compensation that some shops swear by for dimensional stability over long production runs. The OSP control is capable but quite different from Fanuc-based systems—factor in retraining time if your shop is Fanuc-oriented. One thing I hear more about with Multus machines than the other brands is chip management issues. The chip evacuation on some models can be problematic with certain materials and operations.

DMG Mori’s NTX series brings German/Japanese engineering with strong milling capability. Build quality is generally excellent. The Celos control with Siemens 840D underneath is powerful but complex—there’s more capability there than most shops will ever use, and the interface takes getting used to. Support can be inconsistent depending on your region, and parts availability isn’t as strong as Mazak’s network.

Options Worth Paying For

Not every option adds equal value. When you’re comparing used machines at different prices, here’s where spending more actually pays off.

High-pressure coolant through the spindle transforms chip evacuation and tool life on difficult materials. We’re talking 1,000 PSI systems. If you’re cutting Inconel, titanium, or other tough alloys, through-spindle coolant isn’t optional. It’s expensive to add after the fact, so buying a machine that already has it makes sense.

Chip conveyor and overall chip management capability matters more on multitasking machines than on simpler lathes. These machines generate a lot of chips from a lot of different operations—turning chips, milling chips, drilling chips, all in the same cycle. Good chip handling keeps the machine running unattended without bird-nesting or chip buildup that causes problems.

Live tooling horsepower determines what milling you can actually do. Weak live tooling limits you to light finishing cuts and small tools. Look for 10+ HP on the milling spindle if you want to do real material removal.

Probing systems eliminate setup variability. Renishaw is the standard name here. In-process measurement and tool setting probes let you run closer to tolerance limits with confidence because you’re measuring, not hoping. Machines with probing systems installed hold their value better too.

Bar feeder integration makes sense if your parts come from bar stock. Magazine bar feeder capability from companies like LNS, Iemca, or Edge Technologies turns a multitasking machine into an automated cell that can run extended periods without operator intervention.

Options You Might Not Need

Some options add cost without delivering proportional value for every shop.

Maximum tool capacity sounds impressive in specs, but a 120-tool magazine only matters if you actually need 120 tools. If you’re running 25 tools per job, you’re paying for unused capacity that adds mechanical complexity. Match tool storage to your actual needs, not theoretical maximum flexibility.

Built-in gantry loaders are expensive and limit your flexibility. For most job shops, a cobot or portable loader provides automation capability without locking you into one configuration permanently.

Top-tier control packages on new machines can add $25,000 to $40,000 to the price. On used machines, that premium may or may not carry through depending on the market. Make sure you actually need the advanced features before paying extra for them.

Making the Transition Successfully

That two-year learning curve I mentioned at the start? It doesn’t have to take that long if you approach it right.

Simulation software is non-negotiable. CAM systems like Hexagon’s Esprit Edge, Mastercam with proper machine simulation, or the machine builder’s own software let you prove out programs before burning spindle time. You want digital twins that match your actual machine kinematics—not generic simulations, but models of your specific machine with your specific tools. Catching collisions in simulation costs nothing. Catching them on the machine costs spindles.

Start with parts you already know. Don’t bid on new complex work until your team has cut chips on familiar parts. Take existing work that currently runs on your lathe and VMC separately, convert it to the multitasking machine, and learn the machine’s personality. Once your programmers and operators are comfortable, expand into new work.

Using one turret at a time initially sounds backward, but it’s how experienced shops recommend getting started. Learn the machine’s turning capability thoroughly, then its milling capability thoroughly, then start combining operations. Building confidence systematically beats crashing because you tried to do everything at once.

Budget for training beyond the initial installation. The machine distributor should provide startup training, but plan for follow-up. Methods, Morris South, and other distributors offer ongoing education programs. Your programmers will have questions three months in that they didn’t know to ask during installation. Having a relationship with the distributor that includes training pays off.

Control program changes through your CAM software, not at the machine. Shops that make edits at the control instead of in the programming office lose track of what works. The best practice is absolute: all changes happen in CAM, sync to the machine wirelessly, and revision control everything. The California shop I mentioned at the start requires this—no exceptions—and it’s part of why they can maintain quality across ten machines.

The Honest Assessment

Used multitasking machines represent a genuine opportunity for shops ready to grow into more complex work. The technology is mature, the used market has good inventory, and pricing puts capability within reach that would have been Fortune 500-only territory fifteen years ago.

But multitasking isn’t a shortcut. The shops that succeed with this technology commit to the learning curve, invest in programming capability, and choose machines that match their actual work—not their aspirations for work they might get someday.

If your parts need it, multitasking can transform what your shop is capable of delivering. If they don’t, you’re better off with simpler equipment at lower cost and lower complexity.

We see multitasking machines come through our facility regularly. When customers ask me whether this technology makes sense for their operation, I always start with the same questions: What parts are you running? What tolerances matter? What’s your current bottleneck? How strong is your programming? The answers to those questions determine whether multitasking is an opportunity or an expensive distraction.

The machine is just a tool. What matters is whether it’s the right tool for your work.

Key Facts

- Shops report up to 75% reduction in setup time on complex parts using multitasking machines

- Cycle time improvements of 30-50% are typical for parts requiring both turning and milling operations

- Used multitasking machines range from $40,000 to $250,000 depending on age, capability, and condition

- Equivalent new machines typically cost $300,000 to $500,000 or more

- Most shops require 6-24 months to fully utilize multitasking capabilities

- Fanuc 31i-B or newer controls offer significant programming and safety advantages over older generations

FAQ

What’s the difference between a mill-turn machine and a multitasking machine?

Mill-turn typically refers to lathes with live tooling—you can do basic milling and drilling on the part while it’s in the turning spindle. Multitasking machines go further with dedicated milling spindles (often with B-axis rotation), Y-axis capability, and the power to do legitimate machining center work. The line blurs, but true multitasking means you could replace both a lathe and a VMC with one machine.

How many hours is too many on a used multitasking machine?

There’s no universal number because maintenance matters more than hours. A 20,000-hour machine with documented PM schedules and spindle rebuilds can outperform a 10,000-hour machine that was neglected. Look for maintenance records, ask about major rebuilds, and request current geometric testing if possible. Generally, Japanese-built machines (Mazak, Okuma, Nakamura) hold accuracy well even at higher hours.

Should I buy a used multitasking machine or a new entry-level lathe with live tooling?

Depends on your parts and growth plans. If you need true milling capability—complex angles, significant material removal, tight tolerances across multiple features—used multitasking gives you capability that live tooling can’t match. If your milling needs are basic (simple flats, cross-holes, light contouring), a new machine with live tooling offers lower complexity and likely better support.

What CAM software works best for multitasking machines?

Most major CAM platforms support multitasking now. Mastercam, Esprit (Hexagon), GibbsCAM, and the machine builders’ own software (Mazatrol programming, for example) all work. The key is getting a post processor that matches your specific machine configuration and a programmer who understands multi-channel synchronization. Budget for post customization—generic posts rarely work well out of the box for complex multitasking setups.